![]()

![]()

It is perhaps inevitable to want to understand why Stephen and his crew crashed on the night of 24th November 1943. This analysis draws information from a number of sources.

Eraldo Manfroni's Letter

The letter from Eraldo Manfroni [17] provides some tantalising information about the night of 24th November 1943:

"in the evening, during a violent storm, the Polverara countrymen had many times attracted by an accented rumbling of planes, sailing in the rain, wind and thunders. At 2130 hrs about some countrymen of Torre (Polverara) still awake, advised a roaring coming not far away. They observed and they saw flashes of light in the direction of Monte Croce. A few minutes afterwards a group of Torre's countrymen went towards that direction in order to succour if eventually anybody wanted it.....They could scarcely proceed in a straightened manner in account of the explosions of the projectiles:" The account also mentions "On the same night at 2030 hrs, one hour before the happened on the chain of mountains at Polverara west near Bovecchio another fire was noted."

"November 27th. The (German) patrol left the place at about 12 o'clock in the night after a summary reconnoitring and after warned the pressents (sic) of the possible danger of some bombs not explosed (sic)".

"November 28th. During the day we were told that on November 24th at about 8-15 in the evening another English plane had fallen down in the mountains.....near Bovecchio"

Google Earth image showing the Italian town of La Spezia in the bay with the villages of

Polverara and Bovechio in the hills to the North West. The villages are about 3 miles apart.

The 142 Squadron's Operational Record Book [10] indicates that their four aircraft which did not return took off within 8 minutes of each other (LN566 at 1639, LN466 at 1641, HE929 at 1646, and HF694 at 1647). Given Eraldo Manfoni's account that the other crash at Bovecchio happened about an hour before that at Polverara, it may be assumed that the two aircraft were not from the same squadron.

Intriguingly Eraldo Manfoni's letter reports that "many times attracted by an accented rumbling of planes". This could indicate that, for at least some of the aircraft, the area was under the route to the target. His letter also refers to "possible danger of some bombs not explosed (sic)". Unexploded bombs would seem to imply aircraft

routing towards the target rather than away from it.

The Route

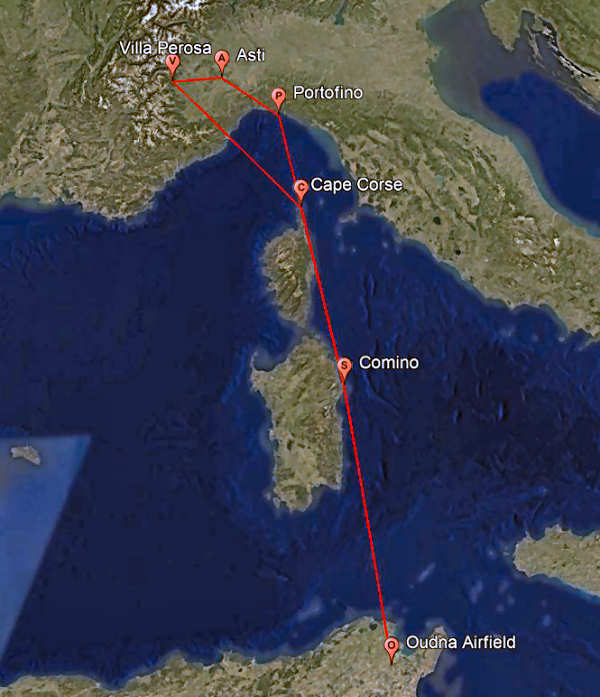

Google Earth image showing intended route to and from Villa Perosa

Information kindly provided by Marco Soggetto [21] provides details of the intended route. Aircraft from 40 Sqn, 104 Sqn and 142 Sqn were to route from Tunisia initially overhead Cape Comino on the island of Sardinia. The next turning point was Cape Corse on the northern tip of Corsica. They were to cross the Italian coast at Portofino and then route to overhead Asti turning westerly towards their target which was at Villa Perosa (about 23 miles south west of Turin). The outward route distance was about 640 miles.

The return route was direct to Cape Corse, thence Cape Comino and back to base in Tunisia (distance about 610 miles).

Had the operation proceeded as intended, the route would have ensured the orderly arrival of bombers over the target and their departure back to base clear of following aircraft. Had the weather been better, it would have been possible to visually check progress along the route and adjust for the effects of winds aloft. The route also avoided anti-aircraft defences at Genoa.

Weather

Page 79 of the 142 Squadron's Operational Record Book [10] records that "The weather was fair up to C.Corse then deteriorated rapidly with 10/10 medium from 2-5000 then another layer of 10/10 from 6000 to over 11000. Rain and icing were encountered above 7000".

In his book "Grandpa's War" [20] Shawn Doyle provides a much more detailed description of the conditions on the night of 24th November 1943 as experienced by his grandfather, (then ranked) Pilot Officer, Bill Turner of 104 Sqn. He was to survive the operation and the war and thus be able to give first-hand details of his experience. The pre-raid briefing included an "expected crosswind of about 30 knots all the way up to Turin. There was also expected to be fairly dense cloud cover". The navigators, mindful of the Wellington's range and speed of about 130 knots tried to complain but their protestations were ignored.

The navigators' concerns were to be proved right. Bill Turner recalled that "The winds started out at about thirty knots, as expected; however, past Sardinia, Bill and the crew hit a strong cold front and the winds accelerated to fifty and then seventy knots". He goes on to say that they were flying in dense cloud, experiencing severe turbulence and became increasingly unsure of their position. Bill persuaded the pilot to descend in order to identify their position. At about one thousand feet they saw the Italian coastline - "somewhere". They continued onwards, again into thickening cloud. At some point Bill, as navigator, asked the rear gunner to drop a "flame float" in order to assess their height above the ground. To their horror it took less than five seconds before it hit the ground. Bill told the pilot to "Pull up, pull up for Christ's sake! Pull up!". With a full load of two tons of bombs the Wellington could not out-climb the hill which came into view ahead. They had no option but to jettison the bombs. They were just able to climb over the hill and thus had a very lucky escape.

Flying

through an extended cold front and into storms, all the aircraft would have been subject to lowering barometric (air) pressure. A reduction of just 1 millibar represents an altimeter error of 30 ft. A typical reduction of 20 millibars would result in an error of 600 feet. In the absence of local observation or accurate forecasting, the crews would have been unable to estimate the extent of the error. Bill Turner's crew had been fortunate to have discovered their reduced height above the ground. Other crews

seemingly weren't so lucky.

Navigation

Unlike bombers operating

from Britain, the aircraft on this operation did not have access to navigational aids such as Gee, Oboe or H2S. In the book "Grandpa's War" [20] it is apparent that navigators would have relied on ded (deduced) reckoning backed up with visual observation of ground features and astro navigation. Given the extended period of flight in cloud and severe crosswind, it was inevitable that aircraft would become lost. Bill Turner does

mention, though, that on other occasions he was able to triangulate his position using Italian radio broadcast stations which continued to operate!

Fatalities

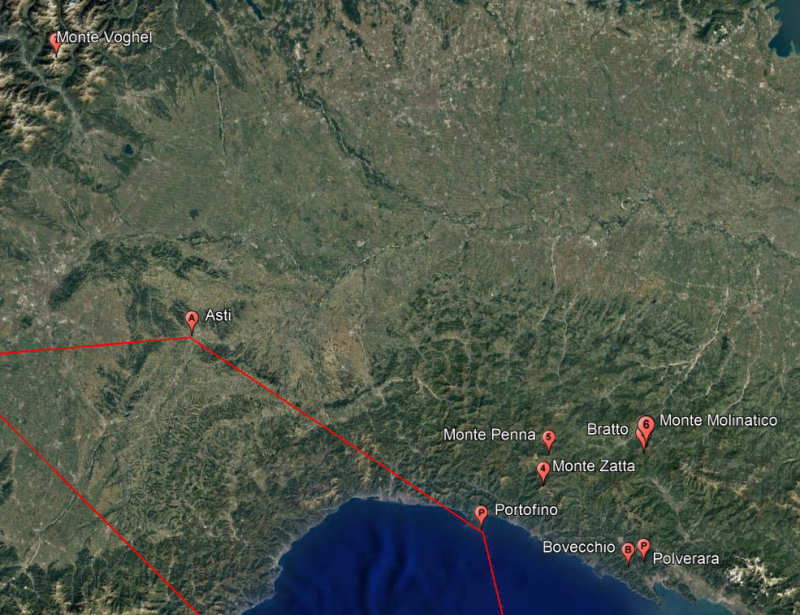

Google Earth image showing the intended inbound route via Portofino

and the seven crash sites.

In addition to the crash site of Stephen's aircraft HF694 at Polverara and that at Bovechio [17], information kindly provided by Marcus Soggetto has enabled the location of a further 5 sites. The map shows the seven locations with details as follows:

|

|

Location | Details |

Source Reference |

|

1 |

Polverara | HF694, 142 Sqn |

[17] |

|

2 |

Bovechio | Not identified |

[17] |

|

3 |

Bratto | HZ552, 40 Sqn |

[22] |

|

4 |

Monte Zatta | Probably DF734, 40 Sqn |

[23] |

|

5 |

Monte Penna | Not identified |

[21] |

|

6 |

Monte Molinatico | HZ552 |

[21] |

|

7 |

Monte Voghel | LN466, 142 Sqn |

[21] |

Given the reported strong wind from the west, the locations of first six crash sites would seem explained. The location at Monte Voghel cannot be so easily explained. In addition to these crash sites, Bill Turner's account [20] includes "Eight of the planes (in 40 Sqn) on the mission did not make it back to base". "Three planes had crashed into Sardinian mountains, their explosions lighting up the terrain for other luckier crews who relied on this morbid illumination to avoid the same fate". It is not clear whether these aircraft were lost on the outward or return journeys.

Examination of 142 Squadron's Operations Record Book [10] for the night of 24/25th November 1943 confirms that 15 aircraft were sent to bomb the Fiat ball bearing factory at Villa Perosa. Of those, four crews perished. A search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's information [18] reveals that all twenty one aircrew (LN566 had a second pilot)had perished and that their remains had been recovered and buried in three different CWGC cemeteries:

|

HF694 "F" |

Sgt Betts DH | Pilot | RAFVR | Staglieno Cemetery, Genoa |

| Sgt Hurnell HP | Navigator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Smith SF | Bomb Aimer | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Bowman CT | Wireless Operator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Barton SA | Air Gunner | RAFVR | ||

|

LN566 "D" |

F Sgt Tyas RC | Pilot | RAAF | Staglieno Cemetery, Genoa |

| Sgt Smith ADJ | 2nd Pilot | RAAF | ||

| Sgt Summers FE | Navigator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Knight WR | Bomb Aimer | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Clark HA | Wireless Operator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt LeBoldus JA | Air Gunner | RCAF | ||

|

LN466 "P" |

F Sgt Wade JG | Pilot | RAAF | War Cemetery Milan |

| F Sgt Lawrence EW | Navigator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Glenwright AC | Bomb Aimer | RAAF | ||

| F Sgt Knapp JF | Wireless Operator | RAAF | ||

| Sgt Carter KR | Air Gunner | RAFVR | ||

|

HE929 "V" |

F Sgt Ouellette SJ | Pilot | RCAF | War Cemetery Florence |

| Fg Of Mair CM | Navigator | RCAF | ||

| F Sgt Armstrong | Bomb Aimer | RCAF | ||

| Sgt Bowering G | Wireless Operator | RAFVR | ||

| Sgt Topp GU | Air Gunner | RAFVR |

At least one aircraft, HZ305 piloted by F.Sgt Bryant of 142 Sqn, ditched and its crew was rescued. It is likely that others also ditched but the crews did not survive.

We can only speculate as to why each aircraft crashed. Clearly the weather was the dominant factor. Bill Turner's account supports the theory that lowering barometric pressure would have contributed. Although he makes no mention of icing, this possibility cannot be discounted since the 142 Sqn Operations Record Book [10] makes mention: a fact which must have resulted from crew debriefs. There remains some doubt whether the Wellington Mk 3 or Mk 10 were equipped with anti-icing systems.

It

would seem that the crews of 17 aircraft perished on this mission resulting in the loss of 86 airmen.

Crash Site Identified

Subsequent to the 2013 revision of this web site, contact was again made with Franco Cozzani who, as a child, had seen the crashed Wellington HF694 in the woods above his village. Franco, in turn, contacted his cousin Fausto Martinelli. Fausto sought the full letter written by Eraldo Manfroni. The combination of the details in the letter, Fausto's intimate knowledge of the woodland above Polverara, and the recollections of Franco, enabled the identification of the crash site at the place known as Venturello. When initially identified, the site was covered in dense undergrowth.

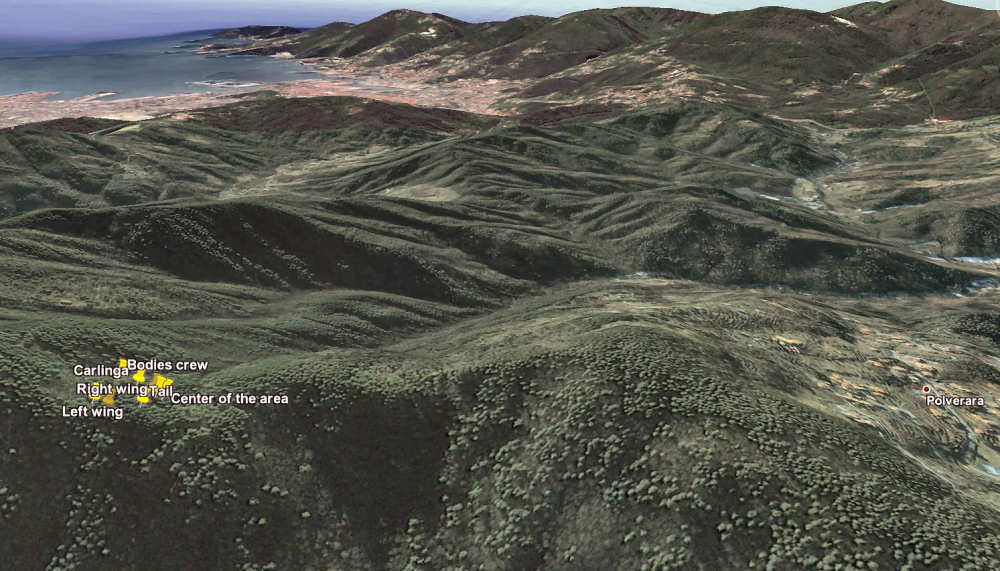

Google Earth image provided by Fausto Martinelli showing the location of the crash site on the ridge at Venturello,

the village of Polverara, and the town of La Spezie in the distance.

Shortly after the identification of the site, Fausto arranged for the site to be cleared and to be surveyed. He also provided this Google Earth image which shows the relative positions of parts of the aircraft and the bodies of the crew [25]. The aircraft came to rest pointing almost South. Ahead of it is the coastal town of La Spezia and to the right is the village of Polverara, at a distance of less than 1 kilometer. Franco Cozzani recalls that several unexploded bombs were evident when he was shown the wreckage in 1943. No debris were evident when the site was cleared in 2013.

In November 2013 a ceremony was held at the site, at which a memorial plaque was dedicated. The memorial plaque is at a altitude of 504 meters (1653 feet) and recorded on GPS as being at 44° 10' 06.6" North, 9° 48' 16.9" East.

![]()